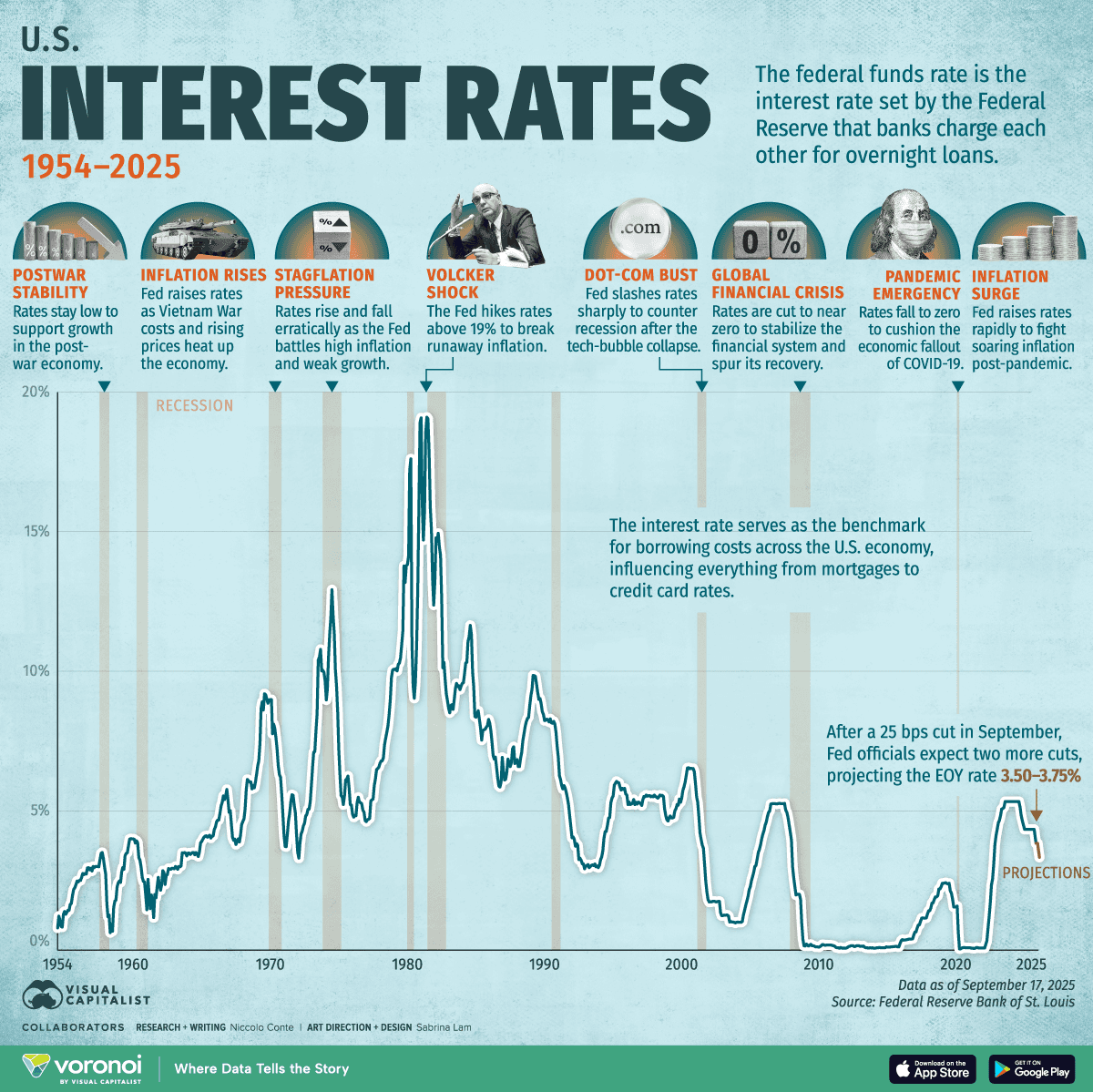

The Federal Reserve cut rates for the third consecutive time in December 2025, bringing the fed funds rate to 3.5%-3.75%. Wall Street analysts praised the move as supportive. Strategists called it prudent risk management. The S&P 500 rallied.

Here's what nobody wants to say out loud: rate cuts don't save economies. They're the monetary equivalent of palliative care—making the patient comfortable while the disease runs its course.

Strip away the narrative and look at the pattern. Since 1990, the Fed has initiated six cutting cycles outside of the pandemic. On average, the economy entered recession just 18 months after the first cut. The correlation isn't coincidental. Rate cuts don't precede recoveries. They precede craters.

The Narrative vs. The Numbers

The story you'll hear from Fed officials goes something like this: "We're normalizing policy from restrictive territory to support the labor market while inflation moderates." It sounds measured. Prudent. Data-dependent.

The reality is messier. Jobs data was already stale in December because of government shutdowns halting official statistics collection. The most recent official figures the Fed had were from September. They made monetary policy for 330 million people using four-month-old employment data during what Powell himself called a "data void."

This is risk management in the same way driving blindfolded is "trusting your instincts."

Meanwhile, the labor market signals that actually matter—the ones happening in real-time—tell a darker story. Initial jobless claims jumped 27,000 to 263,000 in early September, the sharpest spike in months. Past payroll data was revised downward by 911,000 jobs—roughly 75,000 fewer jobs per month than originally reported. Worker confidence in finding new employment if they lost their job? Fell to 44.9%, the lowest since the metric began tracking.

These aren't abstract statistics. They're the economic equivalent of pressure dropping before the storm.

The Historical Pattern: Rate Cuts Confirm, Not Prevent

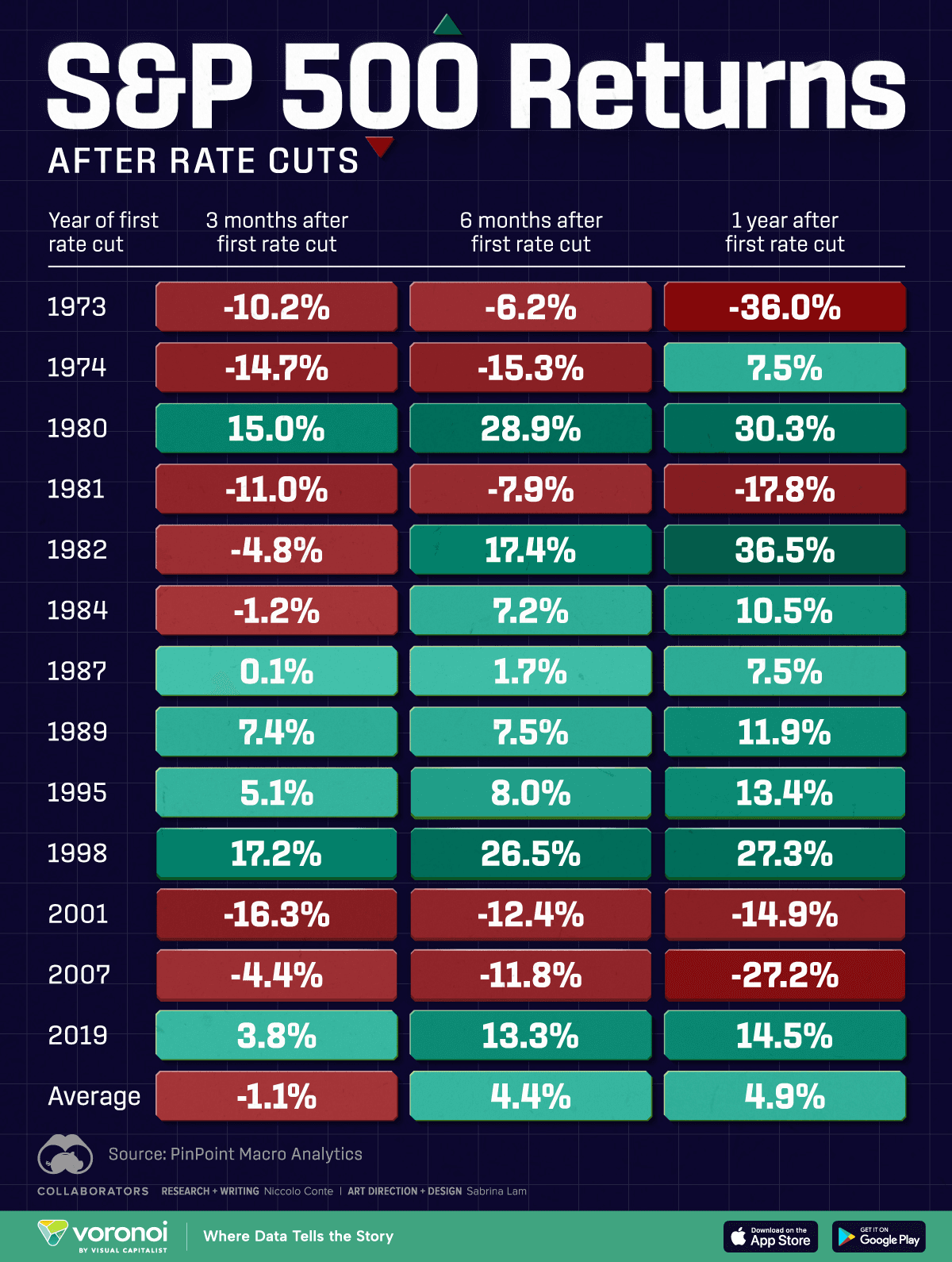

Let's talk about what actually happens when the Fed starts cutting. Of the seven rate-cutting cycles since 1980, only two avoided recession: 1995 and 2019. Both were what economists diplomatically call "mid-cycle adjustments"—insurance cuts when the economy was still fundamentally healthy.

The other five? All ended in recession.

Take 2001. The Fed slashed rates 11 times, from 6.5% down to 1.75% over 12 months. Recession anyway. The S&P 500 lost 22%.

Or 2007. The Fed started cutting in September, initially by just 50 basis points. Financial commentators called it "proactive" and "measured." Fifteen months and 5.25 percentage points later, the funds rate hit zero and we were in the deepest recession since the Great Depression. The market cratered 38%.

The pattern is consistent: when cuts are defensive (economy already weakening), they don't stop the slide. They just document it in slow motion.

Why Cuts Don't Work: The Lag Problem

Here's the uncomfortable truth about monetary policy: it works on a 6-12 month lag. The rate cuts happening now affect lending conditions, investment decisions, and hiring plans that won't fully materialize until mid-to-late 2026.

If the economy is already decelerating—and unemployment climbing to 4.6% with monthly payroll gains down to 22,000 strongly suggests it is—then cutting rates in Q4 2025 is like deploying airbags after you've already hit the wall. Useful for the next accident, perhaps. Irrelevant for the current one.

This is why markets have historically underestimated the depth of cutting cycles that coincide with recessions. Before the 2001 tech bust, markets priced 50 basis points of cuts. Reality: 550 basis points. Before the 2008 financial crisis, markets expected 100 basis points. Reality: over 500 basis points.

The consensus today? Markets are pricing 225-250 basis points of cuts. If history rhymes, that's wildly optimistic.

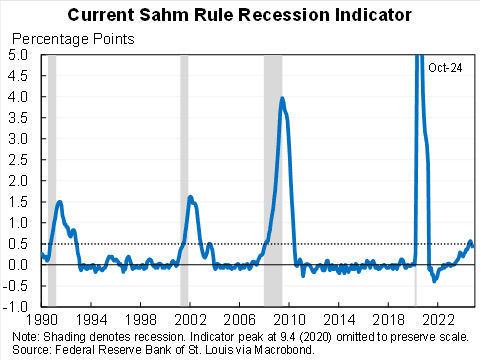

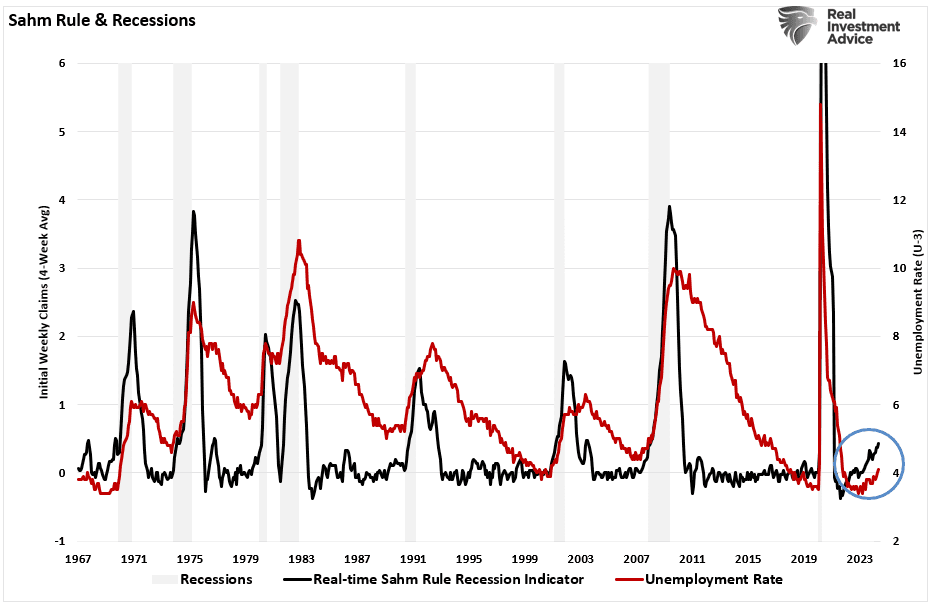

The Sahm Rule: The Canary That's Singing

There's a recession indicator that's been remarkably accurate over the past 70 years. It's called the Sahm Rule, and it's beautifully simple: when the three-month average unemployment rate rises 0.5 percentage points above its low over the past year, you're already in a recession.

The rule has correctly identified all 11 recessions since 1950, typically triggering about three months into the downturn—well before the NBER makes it official and before it shows up clearly in GDP data. It's had exactly one false positive (1959), and even then, a recession followed six months later.

In July 2024, the Sahm Rule triggered when unemployment hit 4.3%. Powell called it a "statistical regularity" rather than a genuine signal. Markets exhaled. No recession emerged immediately, and the narrative became that the rule had finally broken.

But here's what changed: nothing structural. The unemployment rate didn't sustainably reverse. It climbed to 4.6% by November 2025. Average monthly payroll gains collapsed. The rule didn't break. The recession just hasn't been officially declared yet.

Recessions are only named in hindsight. The NBER typically takes 6-18 months to make the call official. By then, everyone already knows. They've lost their jobs, seen their portfolios crater, watched their neighbors foreclose. The only people still debating whether we're in recession are the ones paid to maintain the narrative.

The Unemployment Trap

Employment data has a nasty characteristic: it accelerates in one direction. When people start losing jobs, it triggers a vicious cycle. Unemployment leads to less spending, which causes firms to cut back further, which increases unemployment more.

This is why the Fed obsesses over labor market "momentum." Once unemployment gets moving upward, it's very likely to continue rising. It's not a linear process—it's exponential. You don't gradually slide into recession. You fall off a cliff.

The data shows this clearly. In cutting cycles that led to recession, unemployment jumped an average of 1.4 percentage points within a year of the first cut. That's not a gentle slowdown. That's labor market collapse.

The Paradox: Markets Love What They Should Fear

Here's where it gets darkly amusing. The S&P 500 has posted consecutive 20%+ annual gains in 2023 and 2024—something last seen during the late 1990s. The index trades at 23 times forward earnings, a valuation only reached twice in the past 40 years.

Rate cuts should terrify equity investors at these valuations. They signal the economy needs emergency support. Instead, markets rally on cuts because lower rates theoretically boost present values of future earnings.

This worked in 1995 and 2019—the soft landing scenarios. It spectacularly failed in 2001 and 2008. The difference? In soft landings, the economy doesn't actually need aggressive easing. In recessions, no amount of rate cuts saves overvalued equities from reality.

When recessions coincide with rate cuts, stocks decline 20-40% despite the Fed's actions. The cuts cushion the fall slightly. They don't prevent it.

The AI Exception: Why This Time Might Not Be Different

Bulls argue that AI fundamentally changes the calculus. The Magnificent Seven tech giants now represent 30% of the S&P 500, and they're planning to invest over $500 billion in AI infrastructure in 2026 alone. This spending, approaching 1% of GDP, creates its own economic gravity that might insulate the broader economy from traditional recession dynamics.

Maybe. Or maybe it's the latest in a long line of "this time is different" narratives that preceded every bubble in history.

Consider: MIT research found 95% of organizations getting zero return on $30-40 billion in enterprise AI investment. Yale's analysis documented circular investment patterns—OpenAI funding Oracle while Oracle buys from Nvidia while Nvidia invests in OpenAI. The valuations assume AI productivity gains materialize at scale. History suggests infrastructure buildouts usually overshoot demand by a wide margin.

The 1990s telecom bubble deployed billions in fiber optic cable. The infrastructure was real. The economics didn't materialize for a decade. AI might be similar: revolutionary technology, overhyped timeline, disastrous near-term returns.

What Rate Cuts Actually Signal

When the Fed cuts rates, it's acknowledging one of two realities:

First possibility: The economy is strong enough that modest easing won't cause inflation to resurge, and there's room for "insurance" against downside risks. This is the optimistic interpretation. It worked in 1995 and 2019.

Second possibility: The economy is already weakening faster than the Fed wants to publicly admit, employment is decelerating, and they're desperately trying to get ahead of a deterioration they can see in the granular data even if the headlines haven't caught up yet.

The December 2025 cut? Powell called it an "insurance cut" to prevent labor market weakness from accelerating. That's Fed-speak for "we're worried about option two but don't want to spark panic by saying it out loud."

Insurance is what you buy when you're worried about catastrophic downside. You don't insure your house because you're confident it won't burn down. You insure it because it might.

The Recession Nobody's Calling

Economists surveyed by Bankrate now put recession odds above 35% for the next 12 months—up from 26% at the end of 2024. That's a material increase, but it still implies better than even odds of avoiding recession.

The bond market tells a different story. When rate cuts coincide with recessions, yield curves steepen sharply as long-term rates fall faster than short rates. That steepening has been accelerating.

Meanwhile, Citi's economists expect four rate cuts in 2025—double what markets are pricing. JPMorgan sees the funds rate ultimately reaching 3% by mid-2025, implying over 200 basis points of additional easing beyond current expectations.

These aren't bullish calls. These are hard-landing forecasts. When major banks are projecting aggressive cutting cycles, they're not betting on soft landings. They're positioning for severe economic deceleration.

Why Nobody Wants to Call It

Here's the institutional problem: calling a recession is career suicide if you're wrong, and if you're right, you're just one voice in a chorus that eventually forms. No strategist wants to be the boy who cried wolf, even if the wolf is clearly visible on the horizon.

The Fed can't call it because doing so would accelerate the very dynamic they're trying to prevent. Consumer confidence is fragile. Business investment is cautious. Declaring a recession would be self-fulfilling prophecy.

So we get this dance where everyone pretends the patient is healthy while quietly preparing the ICU.

J.P. Morgan Private Bank puts recession odds at just 20%, citing strong corporate balance sheets and temporary inflation shocks. They excluded the yield curve from their model because it was "flashing false signals." Translation: the data contradicted their narrative, so they changed the model.

This is how consensus forms around soft landing scenarios even as the underlying data deteriorates. Selectively weight the indicators that support the story you want to tell. Discount the ones that don't.

The Clock Is Ticking

Rate cuts take time to work. The December 2025 cuts won't significantly impact credit conditions until Q2 2026. If the labor market is already rolling over—and payroll gains of just 22,000 monthly strongly suggest it is—then we're past the point where monetary policy can prevent the cycle from turning.

The Fed isn't cutting to stimulate growth. They're cutting to prevent growth from collapsing entirely. It's damage control disguised as normalization.

The narrative that "rate cuts are bullish because they show the Fed has flexibility" misses the point entirely. The Fed has flexibility because the economy is weak enough that easing won't reignite inflation. That's not a positive. That's confirmation the growth impulse has already faded.

What History Actually Teaches

Go back through the historical record. Successful Fed cutting cycles—the ones that engineered soft landings—happened when the Fed cut preemptively before major cracks appeared. 1995: Fed cut 75 basis points preventatively. Market rallied 20%. 2019: Fed cut 75 basis points as "insurance." Market gained 28.9%.

Both times, unemployment never materially increased. Growth slowed modestly but never collapsed. The cuts were truly insurance, not emergency medicine.

Now compare that to failed cycles. 2001: Fed cut 550 basis points after the tech bubble burst. Stocks still fell 22%. 2008: Fed cut 525 basis points after the housing market imploded. Market cratered 38% anyway.

The pattern is obvious: rate cuts work when you don't really need them. When you actually need aggressive easing, it's already too late.

The Bottom Line

The Fed is cutting rates because the alternative is worse. That's not bullish. That's panic with a professional veneer.

Markets want to interpret any Fed action as good news. "Hawkish cut? More ammunition for later." "Dovish cut? Economic support." The reality is less convenient: cutting from 5% to 3.5% means the Fed had to reverse 150 basis points of prior tightening because the economy couldn't sustain it.

That's not flexibility. That's failure.

When historians look back at 2024-2026, they won't see proactive risk management. They'll see a central bank that hiked rates aggressively to fight inflation, recognized too late that they'd overtightened, and scrambled to undo the damage as employment fell and growth decelerated.

Rate cuts don't signal strength. They signal an economy fragile enough to need support. And if 70 years of data teaches us anything, it's that fragile economies supported by emergency rate cuts don't typically engineer soft landings.

They land hard. The Fed just makes sure everyone has a parachute—which is lovely until you realize you're still hitting the ground at terminal velocity.

The market will figure this out eventually. Probably around the time the NBER officially dates the recession that started six months ago.

NEVER MISS A THING!

Subscribe and get freshly baked articles. Join the community!

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.